At Element 84, we view advancements in AI and LLM technology as an opportunity to increase our impact and the real-world potential of our work. In early November 2025 we (quietly) released a new set of demos designed to showcase approaches that let users explore the earth with natural language based on earlier unreleased prototypes. We just added some new features on our public demo, including Change Detection and LLM-based embeddings generation, that we’re excited to share.

Try out our new change detection demo

If you’re interested in the prior details that led up to this current release, here are a few blog posts that provide context.

- Building a queryable Earth with vision-language foundation models – March 2024

- Finding Changes on the Earth with Natural Language – December 2024

- Why We’re Talking About a Centralized Vector Embeddings Catalog Now – June 2025

Initial goals: increasing access to geospatial data for all

Over the past year, we’ve evolved Natural Language Geocoding and Queryable Earth from early technical prototypes into two public-facing demos. Queryable Earth demonstrates natural language search over satellite imagery using vector embeddings—specifically enabling users to find changes on Earth (deforestation, new construction, infrastructure development) through simple text queries like “Identify potential mines and quarries in western Massachusetts.”

Similarly, Natural Language Geocoding helps understand and interpret what users are truly saying when they ask spatial questions. Rather than limiting users to a singular place name, it enables more complex spatial descriptions with the help of LLMs to generate graphs of spatial operations, including place lookups, boundary calculations, coastline analysis, unions, intersections, differences, buffers, and more.

The new “search this area” feature allows users to confine their search to the area they are currently looking at, similar to Google Maps.

Over the past year and a half since first discussing these ideas, we’ve continued to dig deeper into practical applications for natural language geocoding, later also researching parallel ideas including vector embeddings and change detection.

Vector embeddings in Earth observation

While vector embeddings are widely used for text, they are not as commonly adopted or recognized as a tool to use with Earth observation imagery. There are, however, some very notable exceptions to this including vector embedding work conducted by companies like Earth Genome, Clay, and Spheer.

Even among groups that recognize the value of vector embeddings with imagery, there are even fewer people who recognize the value of text-aligned vector embeddings based on images. Text is an important aspect of this because it lets us connect user intent and needs to what we actually want to find. This technology can also be combined with other approaches such as a user selecting individual images.

While text-aligned embeddings won’t be as accurate as matches identified manually by a user, they greatly expedite the process with similar results. Without using text-aligned embeddings, users would have to manually create a training set of dozens to hundreds of matches and then use their findings to identify similar items – no simple task!

From visual patterns to semantic understanding

One of the most exciting developments in this release is the integration of LLM-generated image descriptions alongside traditional vision-based embeddings. While our original Queryable Earth demo relied on the SkyCLIP vision model to match visual patterns in imagery, we’ve now added a complementary approach: using Anthropic Claude to generate detailed, natural language descriptions of what’s actually visible in each satellite image and then passing those descriptions through a text embedding model.

SkyCLIP is a CLIP-based model which means it can produce embeddings from images and text in the same vector space. The embeddings capture the semantic contents of the image in a way that we can search with text. We realized that combining a multi-modal LLM like Claude with a text-based embedding model could produce embeddings with the same qualities while taking advantage of the huge advancements in modern LLMs. We wondered how this new approach would compare to a CLIP-based model. The results were promising enough that we now offer both approaches — plus a hybrid option.

To make this concrete: when you search for “houses with swimming pools,” the SkyCLIP model compares your query’s text embedding against embeddings generated directly from the imagery. The LLM approach instead compares your query’s embedding against embeddings of AI-generated captions like “residential neighborhood with single-family homes, several properties with swimming pools visible in backyards.” In the current release, these captions were generated by Claude Haiku 4.5. Both are vector similarity searches, but the LLM-derived embeddings can potentially capture richer scene-level detail.

The “Chip Picker” can be enabled to view the LLM captions

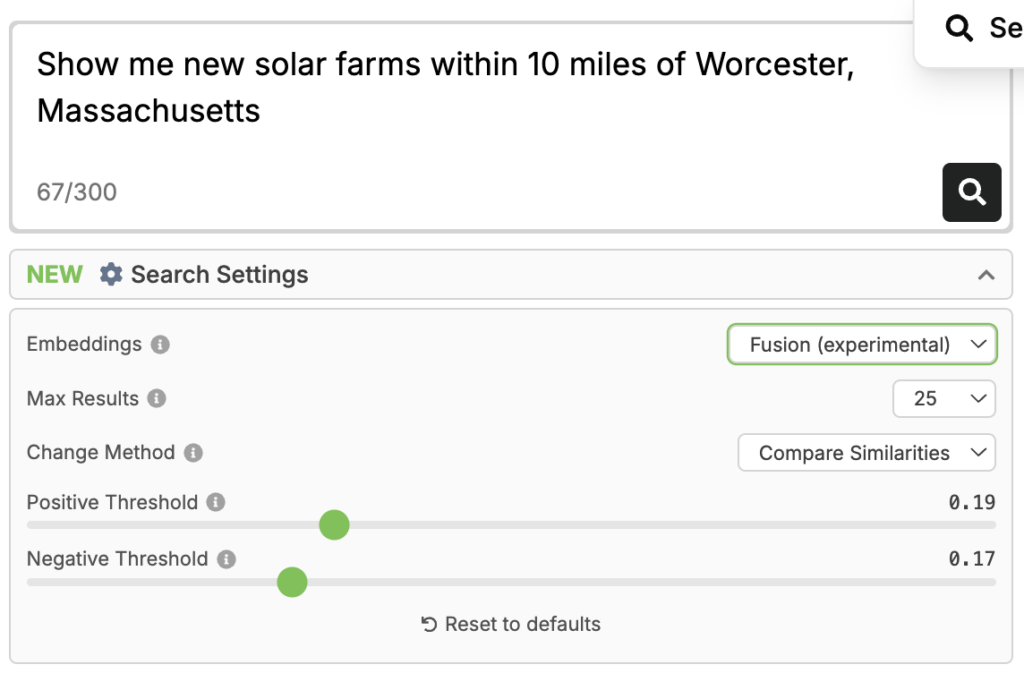

The system now offers three distinct search modes available in search settings:

- SkyCLIP: The original vision-based approach using the SkyCLIP model

- LLM: Search using AI-generated image captions and semantic text embeddings

- Fusion: A sophisticated combination of both approaches that leverages the strengths of visual pattern matching and semantic understanding (now the default)

We’re particularly excited about the fusion approach, which uses weighted reciprocal rank fusion to intelligently combine results from both vision and language models. In our testing, this hybrid method consistently outperforms either approach alone. We’ll dive deep into the technical details of how we generate these captions at scale and combine multiple embedding sources in an upcoming blog post.

The new Search Settings let you pick which embeddings approach is used.

Change detection: experimental feature launch

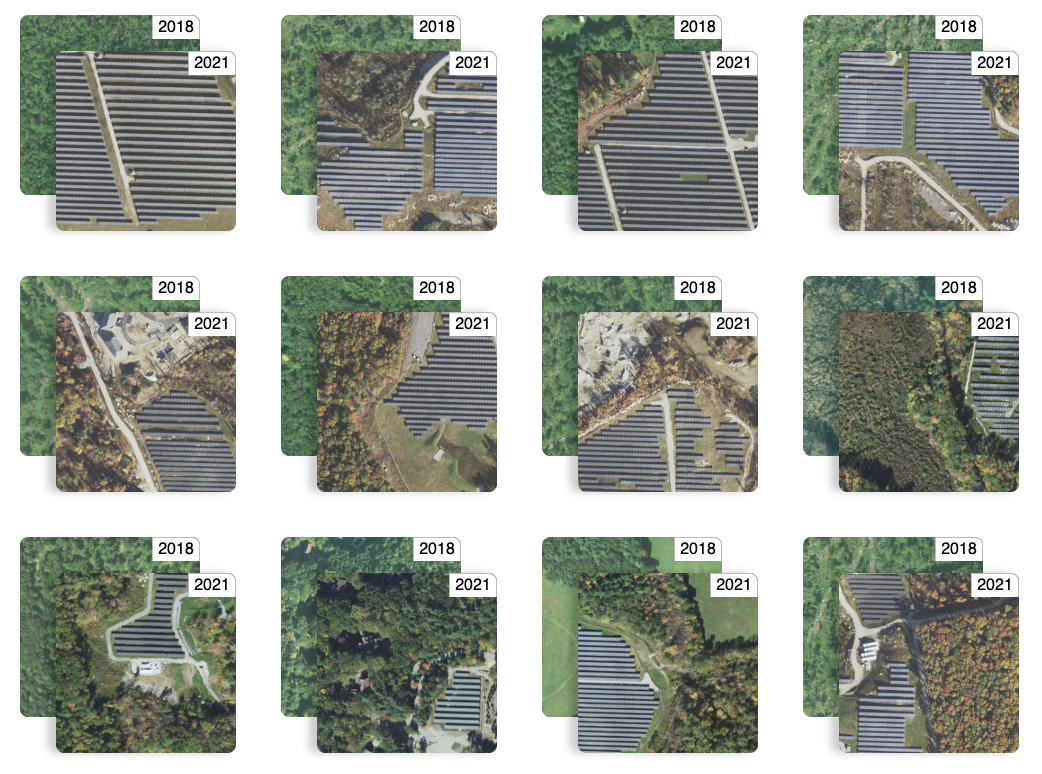

When a user is combing through large amounts of geospatial data, the ability to quickly and accurately compare the same area over time has the potential to hugely expedite research. Through using vector embeddings, details about a set of images are captured by a set of numbers that can be easily compared. Small differences in the number sets mean that the area hasn’t changed much, and large differences indicate semantic changes in the area that may potentially be of note to users.

Jason Gilman presented on this topic at AGU in 2024 and published a corresponding blog post, but outside of that content change detection lived mainly as an internal prototype. Incorporating this work now provides an additional opportunity for users to analyze geospatial data in a customizable and accessible way – and it allows us to experiment with the latest in our LLM and open source tooling stack.

By introducing this capability into our demos, we’ve opened the door for users interested in tracking differences in the data across time. When we moved to incorporate change detection into the demos, the primary goal was to create a working demonstration that combined queryable Earth and natural language geocoding, and then also implemented a way to get feedback about changes between the 2 existing datasets (For example, how did the spread of solar farms within 10 miles of Worcester, Massachusetts change from 2018 to 2021?).

By using LLMs rather than having to rely on humans to review and identify discrepancies between images, and when integrated with queryable Earth, change detection provides new layers of access. The addition allows users to search a fairly large amount of data for specific changes, like new construction, changes to landscape (farmland, forests, water levels, etc) and can even allow for fairly open ended questions to be answered. And, perhaps most significantly, these comparisons do not require super specific queries like would be required if you wanted to compare something on your own.

Who are the demos for, and how can they be used?

Since we unveiled the demos a few months ago, we’ve loved seeing the varied queries users are submitting. Here are some of the use cases we’re most excited about:

Environmental monitoring and conservation: Users can track deforestation patterns, identify areas of habitat loss, monitor coastal erosion over time, or detect changes in water bodies and wetlands. Organizations can search queries like “show me forest areas that have been cleared” to prioritize conservation efforts.

Urban planning and infrastructure development: City planners can monitor urban sprawl, identify new construction activity, track infrastructure improvements, and understand development patterns. Queries like “find all new residential developments within 10 miles of Boston” become trivially simple, enabling data-driven planning decisions.

Energy transition tracking: Users can identify renewable energy installations such as solar farms and wind turbines, monitor their growth over time, and analyze the pace of energy infrastructure development across regions.

Disaster response and insurance assessment: After natural disasters or severe weather events, interested parties can quickly identify areas of change and potential damage. Insurance companies can assess risk patterns by analyzing construction in flood-prone areas or wildfire zones.

Real estate and market analysis: Developers and investors can identify emerging areas of development, understand neighborhood evolution, and spot opportunities by searching for patterns like “new commercial construction” or “areas of recent development.”

Want a custom Queryable Earth implementation?

Ultimately, this project is still a prototype. If you are interested in learning more from our team about setting up a custom implementation for your specific project needs, we’d love to chat. Our work on these demos is designed to provide a resource for the community, and to potentially inject new life into a variety of projects that could benefit from this technology.В

You can check out the demos, including our new change detection feature, here. Stay tuned for more updates to the Queryable Earth ecosystem, and don’t hesitate to get in touch if you have any questions or ideas for future development in this area.В

What’s next?

As we continue to develop and expand this set of demos as a community resource, we look forward to learning about a variety of additional use cases and possible future implementations. The combination of queryable Earth and natural language geocoding represents a pathway for users to greatly simplify and streamline the dataset search and discovery process, and a comparison through change detection is often a lot more compelling than finding a single image that matches a query.

If you’re excited by these demos, stay tuned! Our team is already developing the next iteration of these tools, and we plan to integrate an agent into the platform. With these improvements, a conversational UI will allow for ongoing discussion and provide additional insight into the behind the scenes as the program answers questions. For more information on this work, or to chat with our team directly, find us on our contact us page any time. We’re always interested to hear about how you’re thinking about our work, and how these tools are contributing to your specific use cases.