In an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, Commander Data (an android), creates a new android, Lal. His creation, paralleling the new generation of AI-assisted tools, extends her creator’s capabilities but also begins to operate autonomously. Lal begins to learn, evolve, and act independently, faster than Data can fully guide her. Eventually, she is overcome by a rapid succession of errors, one after another, where the system is overwhelmed by the equivalent of unpayable technical debt, and effectively dies.

Open-source software is facing a new kind of pressure — not from funding or standards debates, but from tools that are now building tools, often beyond our oversight. While this shift affects the entire open-source ecosystem, the geospatial domain offers a case study on the role of subject matter expertise in the world of AI.

The Value of Expertise

There is a pervasive anxiety that AI will devalue software development or replace software jobs. I argue the opposite: true subject matter expertise is becoming more valuable, not less. As AI tools like Copilot and ChatGPT shift from simple autocomplete to creating complex code, they create a new risk: generating abstractions faster than humans can review them. As the gap widens between the quantity of AI-generated code and our human capacity to review it, we must rely more heavily on subject matter experts to set standards and prioritize correctness over plausibility.

The need for this expertise is particularly acute in the geospatial domain. While the “geospatial isn’t special” movement successfully pushed for integration with general-purpose infrastructure, AI often reveals that geospatial is special. Datelines, projections, and topology don’t generalize well in training data. AI is reshaping how our software is written, accelerating a fragmentation effect that makes deep expertise critical. By creating an Illusion of Completeness, these tools default to vibe-coded fragments, bypassing robust libraries and creating a sea of noise.

This is not a threat but a call to action. We must move up the stack—evolving our role from just writing code to designing the foundations the new AI agents will be built on. This requires both an immediate triage to fortify the geospatial signal and an effort to build a new ecosystem of machine-readable specs.

How Did We Get Here?

In just four years, we went from Copilot’s sophisticated autocomplete (2021) to ChatGPT’s conversational coding (2022), and then to GPT-4’s ability to reason across files (2023). By 2024, massive context windows and specialized models fundamentally changed the workflow. We stopped just asking for snippets and started dumping entire repositories into the prompt context for refactoring, test generation, and scaffolding. Scaffolding new repos with LLMs is now the default.

Now, we are entering a correction phase. Tools like GitHub SpecKit act as a counterweight to the years of loose vibe coding, attempting to force AI-generated code to align with rigid, human-authored specifications before a single line is written.

Geospatial Isn’t Special (Until It Is)

For years, our community has pushed to “make geospatial not special” by integrating it into general-purpose data infrastructure. We’ve seen this succeed in formats like GeoParquet, where the community added spatial metadata to the Parquet format rather than inventing a new, isolated one. It’s a strategy that prizes reuse and efficiency.

But that efficiency depends entirely on the deep domain expertise encoded in our libraries. We can treat spatial data like “just data” only because tools like GDAL and PROJ handle the complexity for us.

AI treats geospatial as “not special” by default, generating generic solutions that fail on complex realities. It has no domain expertise and will generate generic, vibe-coded solutions that fail spectacularly on the complex realities it doesn’t understand.

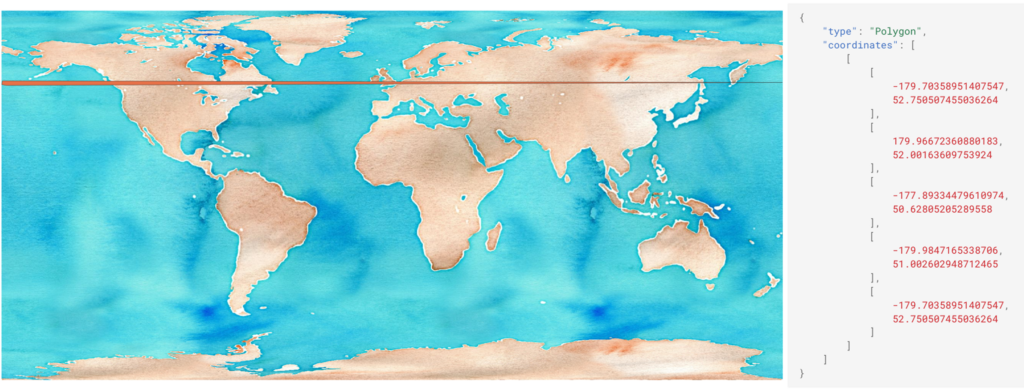

The Antimeridian Example

The antimeridian Python package, written by Pete Gadomski, encodes the complex, non-obvious logic for handling AOIs that cross the International Date Line or the poles. It’s a special problem, solved by experts, in a robust library. AI assistants, unaware of this package, will always generate a bespoke fix that is brittle, naive, or flat-out broken. The vibe solution fails the real-world test, proving that in the moments that matter, geospatial is special.

The Illusion of Completeness

A main problem of AI-assisted coding is that it creates an illusion of completeness. The generated code looks functional. It runs. It satisfies the developer’s immediate prompt. But it silently skips the hidden, non-obvious engineering required for robust, scalable, and secure software.

This isn’t a new problem. Shipping untested, bespoke code instead of using a proven library has always been foolish. The new problem is that AI makes this foolishness scalable, effortless, and invisible. It is an accelerant for bad engineering. Various articles are already speaking about this dilemma, including how amateur vibe coders are seeking support from “real programmers” and diving into real-world production disasters caused by vibe coding.

To return to our Star Trek analogy, this is Lal’s failure. The vibe-coded fragment is Lal, an entity that appears fully functional and evolved, but has skipped the foundational, boring architecture required for long-term survival.

Fragmentation

This illusion has the potential to break open-source. For decades, the path of least resistance for solving a hard problem was to find a shared library. You searched, found GDAL or pandas or pygeoapi, followed some examples, and effectively outsourced the complexity to a community of experts.

With AI, the path of least resistance has shifted. It is now faster to ask an LLM to write a function that does X than it is to find and learn a library. The result is a potentially massive fragmentation effect. Instead of one robust package maintained by the community, we are heading toward a future with thousands of slightly different, hallucinated implementations scattered across code bases.

I saw this on a recent project where we needed a features API. A developer explicitly vibe coded it, producing code that appeared to work perfectly. It handled the happy path. But it completely bypassed the ecosystem. They hadn’t just written code; they had accidentally opted out of OGC compliance, CQL filtering, and performance optimization—features inherent to tools like GeoServer, pygeoapi, or TiPg. The community has a foundation, but the AI gave them a snippet which felt like enough.

We’ve Been Here Before

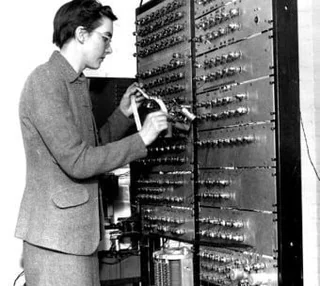

We are not the first community to face this. In the 1950s, Kathleen Booth wrote the first assembly language. The “priesthood” of assembly programmers, domain experts who held arcane, intimate knowledge of the hardware, were confronted by the first “AI”: the compiler.

Their arguments might sound familiar: the new tool was untrustworthy (“How can I trust it?”) and that its output was inefficient (“I can beat the compiled code by hand”). They were technically correct, but they missed the point. The compiler won because it was good enough and it freed developers from worrying about hardware registers, allowing them to focus on complex logic and moving their value up the stack.

This suggests a path forward. Here, moving up the stack means to move from writing code to designing the systems that guide the code’s generation. The move from assembly to compilers created a whole new ecosystem of high-level languages, compilers, linkers, and debuggers. We need to help build the new ecosystem.

Potential Ways to Reduce Fragmentation Due to AI

Fragmentation is the passive, default outcome. We need to improve the signal and improve interoperability while also building the foundations for the new ecosystem.

1. Increase the Signal

First, we must build and improve what we already have to increase our human-generated signal amidst the noise. This means doubling down on our foundational libraries and surrounding them with clear, comprehensive documentation, real-world tutorials, and test suites that encode our domain knowledge.

The core principle is simple: things that make it easier for humans also make it easier for LLMs. There is no excuse for a bad README anymore. We can, and should, use AI to help write them. If the documentation is logical and the test suites capture edge cases, the LLMs ingest this signal and the generated code improves.

2. Champion Standards

Interoperability is critical in the age of AI (perhaps even more so now than before) because models default to using the tried-and-true interfaces they recognize from their training data. If the training data includes a thousand different implementations, no single interface is seen as authoritative.

A standard provides well-documented details and implementations that reinforce consistent behavior, providing a single specification for reference. This makes the AI more likely to generate functioning code. Even better, it enables the model to leverage existing clients as dependencies rather than creating its own from scratch.

3. Build the Foundry

I’m inventing a term here, because I don’t think we have a good one for this yet. The Foundry is the software ecosystem where we stop writing code and start creating specifications. This may eventually take the form of something like GitHub “SpecKit,” or something different. These specs are the descriptions and constraints that new AI “compilers” will use for implementation (perhaps even in their own optimized, internal languages).

Writing Python code will one day seem as quaint as writing assembly language does today. Instead, The Foundry represents how we will interface with AIs to design software in the future. Our value lies in using domain knowledge to create these specs, as we move from software developers to software designers.

Where This Leaves Us

This doesn’t have to play out this way, but it also won’t fix itself. Fragmentation is what happens when speed is rewarded and judgment is optional. AI doesn’t ignore libraries or standards because it “doesn’t know better”; it does so because our ecosystem often makes plausible-looking, bespoke code cheaper than engaging with the hard parts.

Open source has always depended on a small number of shared libraries and standards that capture domain knowledge. When those foundations are easy to find and well-documented, both humans and machines reuse them. When they are obscure, underspecified, or poorly maintained, reimplementation becomes the path of least resistance, and fragmentation follows.

Standards and specifications aren’t exciting, but they matter. They’re the difference between “whatever the model guessed” and behavior the community has actually agreed to support. Without them we get a thousand slightly different implementations, all of which someone has to maintain, or abandon, at the cost of increasing the noise. This is an ongoing process, so if you have ideas or thoughts on this topic reach out to our team.